Baltimore and Institutionalized Violence

Storm clouds over Baltimore around 6:30pm Monday, April 27 2015. Flames and broken glass intentionally left out.

Baltimore is in the thoughts of many people all over the world today. Last night’s violence is now another page in the annals of the often tragic relationship between people of color and the police in the United States.

I am a historian of institutionalized violence and I live in Baltimore. It is impossible for me to stand aside and not reflect on recent events. Indeed, if there were ever important roles for a historian to play in troubled times – reflection is probably chief among of them. I study many things: science & technology, economic and political history, the history of war and genocide in Nazi Germany, and other related subjects. Even though it is not my area of specialization, when you pursue multiple advanced degrees in US history, a considerable amount of time is spent studying the legacy of racism in America – particularly as it relates to African-American slavery, Jim Crow, and the defacto and dejure discrimination that still plagues the country. It’s unavoidable. Take my qualifications for what you will. Alexis de Tocqueville once wrote that the frustrating beauty of American thought was that people were free to be their own experts. In any case, some will come here seeking perspective and that is provided below.

**

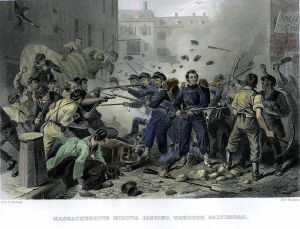

First, the precedents: Unfortunately, mob violence is not new to Baltimore. In April of 1861, there were clashes between Union troops traveling through Baltimore on their way to Washington, D.C. and pro-Confederate militias. About a dozen people died. John Merryman, one of the militia leaders, was later arrested and denied legal counsel. Despite the need to prevent further sabotage to the Union war effort, historians still debate the wisdom of the suspension of habeas corpus at that time – a fateful moment in the expansion of police power in America. Today, we have unconfirmed reports that protesters are also being held without representation.

An outpouring of specifically black discontent is also not new. When the news of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination hit Baltimore in the first week of April 1968, black citizens rioted for several days. Six people died and hundreds were injured.

April seems to be a bad month for Baltimore.

For the first time since 1968, Governor Hogan has called in the National Guard to deal specifically with black discontent. Just like in 1968, a state of emergency and curfew has also been declared. And, just like in 1968, the words “they are burning their own neighborhood” were on the lips of white onlookers. Why does the cycle continue?

**

First, some facts: There was a largely, peaceful protest in Baltimore on Saturday, April 26th, 2015. For the record, this protest was planned because of the death of Freddie Gray, who was arrested for making eye contact with the police (no joke). He was in good health when he was arrested, but when he arrived to booking, 80% of his spinal column had been severed. He died shortly after. Because of the national prominence of police brutality in recent months and years – which include the murders of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown, the #blacklivesmatter movement, the Dream Defenders, and other national groups have endeavored to organize large scale protests to focus national attention on police brutality and the murder of black people. Only a few weeks earlier on April 7, Walter Scott was shot in the back and killed by a South Carolina police officer in a traffic stop. A bystander caught the action on their phone, including the officer planting a weapon on Scott’s body to justify his murder.

It seemed appropriate to protest yet another unjust death. It appears as though the April 26 march started fine and then devolved into violence as it approached the baseball stadium. Why? Because white attackers provoked the crowd.

Didn’t hear this part of the story? Here’s some pics:

What did the police do when violence broke out? They attacked the protesters. Which then provoked a reaction against the police – who were, of course, the reason for the protest in the first place. News outlets reported property damage and violence to police vehicles, while mostly ignoring why this event occurred. Ignoring the point of the protest and the desire for redress only increased frustration and anger of the black community and their allies.

Then came Monday, April 27th.

The day started with a “credible threat” to Baltimore Police, who claimed that local gangs had joined forces to attack them. This became an excuse to come out heavily armed and shut down public transit. Ironically, what had actually occurred was a truce between gangs to help keep the peace. You can watch an interview with some of the gang leaders involved discussing their plans to help create calm and unity here. Students at the predominantly black (and aptly named) Frederick Douglass high school had planned a walkout and a protest, and found themselves immediately beset by riot police and a lack of means of transportation to get home. The situation exploded.

In case this needs to be clearly mentioned: Neither the presence of riot police nor the shutdown of city transportation needed to have happened. The responsibility to avoid further violence and provocation of an already volatile situation was in the hands of adults not the children who reacted to the situation.

**

This is where most people know the rest of the story. Buildings burned. Businesses were looted. There were hundreds of arrests.

If you needed more irony, the property damage occurred in close proximity to the areas that were damaged in 1968. Some of those parts of Baltimore were never rebuilt. And this is really the main issue. When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered, he was working on “The Poor People’s Campaign” in 1968. King realized that economic justice was closely tied to racial justice. If people are able to provide for their families, the fear, hate, and racism of one group being pitted against another to fight over scarce resources begins to become more irrelevant. Here is noted King scholar Adam Fairclough on this topic:

Blacks were not simply confronting irrational prejudice on the part of individuals but also systemic economic exploitation by the majority. [King] likened the ghettos to internal colonies: whites controlled an perpetuated them because they profited from them. The movement’s demand to end slums, he now realized, had challenged powerful economic interests. “You can’t talk about ending slums,” he warned his staff, “without first seeing that profit must be taken out of slums. You’re really…getting on dangerous ground because you are messing with folk then. You are messing with Wall Street. You are messing with captains of industry.” The white backlash, he contended, had only a superficial connection with the spread of black rioting: white racism was coming out into the open because whites saw their privileges being threatened. [emphasis mine. p. 110]

Unfortunately, it should not be a surprise that economic injustice in the black community is not a new issue; however, it is complicated by the racial dynamics in Baltimore where we have a black mayor and a black police commissioner blaming “criminality” and using respectability politics to deny people their longstanding grievances. If you live in Baltimore, you don’t need to watch The Wire to know that there are whole sections of the city that have been abandoned by civil society. Baltimore has become the land of crime statistics. By focusing on assaults, burglaries, and vandalism, those that have done well can abdicate themselves of helping those that have been left behind. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, in his book, The Condemnation of Blackness, explains it this way:

By illuminating the idea of black criminality in the making of modern urban America, it becomes clear that there are options in how we choose to use and interpret crime statistics. They may tell us something about the world we live in and about the people we label “criminals.” But they cannot speak for themselves. They never have. They have always been interpreted, and made meaningful, in a broader political, economic, and social context in which race mattered. The falsity of past claims of race-neutral crime statistics and color-blind justice should caution us against the ubiquitous referencing of statistics about black criminality today, especially given the relative silence about white criminality. [p. 277]

And white criminality is the real issue here. Although there is obviously an intersection of race and class problems in Baltimore, the reigns of power in the US are still primarily held by white people. Furthermore, not all crime is illegal. The reason there are poverty ridden areas and crumbling infrastructure all over America is primarily due to the offshoring of large amounts of money by the richest individuals and companies. Draining all the resources that were meant to support schools, hospitals, and programs to help the most vulnerable among us is morally reprehensible even while it remains (somewhat) legal. The continuation of this process, which has only accelerated in recent years, will exacerbate the unrest in impoverished black communities. The police will continue to deal with the problem the only way they know how: with more force. Thus, the cycle of violence may continue.

**

This is not the only story, though.

Because then April 28th happened.

People from all over the city came to clean up the areas that had been damaged overnight. So many Baltimorians came to help, that there were not enough projects for them to work on.

What will befall Baltimore tonight? No one can say. But I can tell you this: While economic opportunities are limited, while media focuses on property damage rather than the grievances that need to be heard, while officials abdicate their responsibility to calm people, and instead provoke them in an already volatile situation, this won’t be the last uprising. There is work to be done: Tackling big problems like climate change could bring about huge economic opportunities, which have the potential to mitigate long standing problems. Education and information literacy can help us improve our news media and communication skills so we are better equipped to understand the problems we face. Finally, we need to listen to the people, rather than judge them. Of course, that’s just a suggestion.

Reblogged this on A R T, t h e M E T A V E R S E, & E V E R Y T H I N G and commented:

Mandatory reading.

Reblogged this on Catskill bob's Blogosphere.

Very educational thanks for sharing this 👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏

To those of you just visiting: Guess what? I moderate all comments on this blog! That means that your obnoxiously obtuse, willfully ignorant, and blatantly racist commentary will be nowhere to be found! Sorry you wasted your time. Well, kind of sorry.

Ok, I’m not sorry at all. Please take it elsewhere – and have a nice day.